Many questions were raised back in 2010 when the Conservative manifesto committed an incoming Tory administration to train 5,000 community organisers; the voices asked many things but amongst them was a concern about how this new ‘army’ (yes, sadly that was the language used!) would relate to the existing community sector and particularly the uncounted number of local residents struggling with voluntary capacity to make their community better. The manifesto made it clear that the Conservatives were looking to develop a new dynamic look to their community-facing policy.

Cuts and Challenge

Alongside the cuts to public spending, they wanted to challenge many of the assumptions that the Labour government had instilled during their thirteen years in office. Amongst these was a distinct antipathy to community development and particularly to dependence on state funding for work on empowerment, diversity or cohesion. At the same time, David Cameron had staked significant personal capital on his Big Society concept and was determined to press ahead to change the way citizens relate to the state. Their Lib Dem partners in the new Government were fully in favour of this change in direction so it became a central pillar of the new administration.

This week, I have had several opportunities to reflect on what is distinctive about organising. But how different in practice is community organising from community development? Are they cousins, siblings, twins or identical? As different as apples and oranges? Or rather like the chicken and egg? How far can we get without descending into petty arguments about terminology?

Such questions are beset with difficulties. There are numerous different styles and cultures of community development and of community organising. They have never existed in separate worlds and it is clear that in the skills and knowledge of practitioners there is huge common ground. The community development scene in the UK has been on the whole developing without regular insights from community organising; in America, similarly the impact of community development on community organising has been weak. And no doubt the cultural differences between the UK and the US has played its part in driving a wedge between the two.

Two histories

You also have to take account of the different trajectories of development of the two terms on either side of the Atlantic. For Americans, community development is often about quite large institutions of service delivery – Community Development Corporations (cf. UK Housing Associations) – whilst for the Brits, it has term adopted by many to reflect their concern for grassroots equality and justice. Efforts to develop community development as a professional discipline have often been ground down by government indifference and disputes between agencies. Community development has remained on the side-lines in most UK policy making whilst in the US it has been mainstreamed in a highly bureaucratic way.

Both schools of community-facing activity have developed over time too. Some people read Saul Alinsky writing in the 1970s as though his were the final words on organising. In practice, organising has a wealth of literature developing, refining and in some cases refuting Alinsky. Similarly, the academic purist or policy officer in UK community development circles often holds a pretty radical view of their discipline whilst the practice of local workers is often constrained by real resistance to change amongst their peers and in the community itself. Many Labour government programmes had significant investment in community development staff and training but failed to prove the value of the on-the-ground resources so devoted. Practice and theory don’t always inform each other, especially in the eyes of a sceptical observer.

Good quality, up-to-date practice of both schools of community activity is difficult to find and to compare accurately. But I would point to some distinctive aspects of community organising which set it apart – in my view – from the majority of UK community development.

Fundamental conflict

First, community organising has always been politicised and propelled by a concern for challenging the status quo. The possibility of collaboration with the state or of ‘partnership’ has always been anathema to community organisers – which raises some difficult questions about a government-funded training programme! This stance derives from a deeply polarised view of society echoed in the Occupy movement of today. Alinsky pointed to the Haves (1%) and the Have-nots (99%) and organisers today continue to emphasise their essential and abiding opposition. Society today is highly polarised between an ultra-rich elite who run things and the impoverished mass who have a smaller share each day of both power and resources.

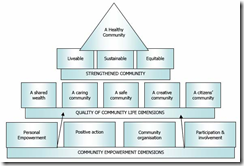

Some versions of UK community development have adopted this view of society in fundamental conflict and their practice has been enhanced by its politicised content. However, most practitioners whilst inspired by such rhetoric have been unable to implement such an approach with much rigour given the dependence on establishment funding – government, trusts and rich individuals. Since 1980, it has also been a difficult phase of British political life to engage in radical community development when the freedom to protest against ‘partnership working’ has been so denied. Few in community groups want to engage with such tendentious politics fearing fearsome debate and crippling inertia. (The diagram comes from Achieving Better Community Development (ABCD) on the Scottish Government’s website)

Some versions of UK community development have adopted this view of society in fundamental conflict and their practice has been enhanced by its politicised content. However, most practitioners whilst inspired by such rhetoric have been unable to implement such an approach with much rigour given the dependence on establishment funding – government, trusts and rich individuals. Since 1980, it has also been a difficult phase of British political life to engage in radical community development when the freedom to protest against ‘partnership working’ has been so denied. Few in community groups want to engage with such tendentious politics fearing fearsome debate and crippling inertia. (The diagram comes from Achieving Better Community Development (ABCD) on the Scottish Government’s website)

People vs Privilege

Secondly, community organising is fundamentally about pitching the power of the people against that of privilege. For many in community development organisations, their appeals to the powerful for better treatment of their low-income community are based on rational argument, evidence and fellow feeling, on liberal sentiment and on occasions on pure pleading. Community organisations on the other hand are able to bargain with powerful interests by offering attractive inducements and threatening real world loss of status and power. By threatening to withdraw their cooperation, the 99% are able to hold the 1% to account. Such a power focus makes the internal democracy of the organisation a central plank of their legitimacy.

Community organising is well suited to tackling structural injustice but it also has its drawbacks. Pressing for a change of policy can be achieved by the pressure of numbers but taking control of the resources to deliver that policy requires specialist expertise and a very different paradigm. Community organising is best suited to local neighbourhood work where people can have face-to-face relationships of trust and respect. It does not translate well into citywide or national multi-neighbourhood networks without becoming blighted by overbearing bureaucracy. Community development has proved itself better able to implement large programmes but in the process, all too often becomes dominated by the programme logic of partnership and loses all dynamic links with its actual community.

So in the UK what is the relationship between community development and community organising? For many stalwarts of the community development world, the political background – and especially the draconian cuts to frontline services – makes community organising suspect at best and loathed at worst. For those committed to community organising, the the allegiance of many in community development to partnership with the state apparatus makes them unpalatable fellow travellers. The dialogue between these two models of action in the community needs to be more generous and carefully framed. Only then will the strengths of each be recognised and important lessons drawn for both parties.

Resources

Randy Stoecker (2001) Community Development and Community Organizing: Apples and Oranges? Chicken and Egg? from the Online Conference on Community Organising at http://comm-org.wisc.edu

Aaron Schutz (2008) Core Dilemmas of Community Organizing: What is Community Organizing? What isn’t Community Organizing? from Education Action now at Open Left http://openleft.com/user/educationaction

Dave Beckwith with Cristina Lopez (1997) Community Organizing: People Power from the Grassroots from The Online Conference on Community Organizing at http://comm-org.wisc.edu

Margaret Ledwith (2011) Community Development: A Critical Approach Policy Press

Alison Gilchrist and Marilyn Taylor (2011) A Short Guide to Community Development Policy Press

Meredith Minkler (ed) (2005) Community Organizing and Community Building for Health (2nd Edition) Rutgers University Press

James DeFilippis, Robert Fisher and Eric Shragge (2010) Contesting Community – The Limits and Potential of Local Organizing Rutgers University Press

Douglas R. Hess (1999) Community Organizing, Building and Developing: Their Relationship to Comprehensive Community Initiatives from the Online Conference on Community Organising at http://comm-org.wisc.edu

Note: I have restricted my discussion to the pattern in the UK and US. This is where my knowledge is most secure. I am very aware that my readers may be able to comment from experience in other global contexts such as India, Canada, Hungary, Brazil or Australia where the two traditions flourish alongside each other. I would welcome your views.

hi Mark, just responded on CDX website but here’s my thoughts :

Baby D and Baby O are sitting in their pram, and while no one is watching one of them hits the other one over the head with a rattle. The other retaliates, hitting the fellow occupant of the pram with a rubber hammer. All this kafuffle jolts the pram and gives it momentum; the pram starts rolling down the hill, heading for the concrete stairs (it’s Battleship Potemkin, innit) . Mr 1% waves and smiles at them as the pram bounces and pitches down the stairs. “Don’t worry”, cries one of the babies, “the 99% will save us”. But at the next step are the 10% senior managers and politicians and their advisors, whose eyes are elsewhere as they fawn on Mr 1% and try to trip each other up as they clamber up the stairs– and even worse, one of the 10% hates both babies and gives the pram an extra nudge . “I think that was a psychologist” screams one baby to the other. The pram hurtles on, heading towards the 40% who are carrying flat screen tellies and chesterfield settees up the stairs as they seek to attain the comfort zone nearer Mr 1%. “No help there then” cries one of the babies, “but we’re heading for the real people so we’ll be saved”. But as they lurch across the stairs they see the 49% at the bottom of the stairs are struggling with their own prams, bumping into each other and not looking up to see what might be coming next. On the sidelines they see 1% of the 49% filming their descent on mobile cameras, while another 1% are writing books about the tendency of prams to descend quickly down staircases, given a nudge. “There’s ho help there – it’s up to us”, both babies cry simultaneously – and one baby jams the rubber mallet in the wheel on the right, and the other baby jams the rattle in the wheel on the left, and they bring the pram to a shuddering halt, sending them flying through the air to land softly on a physicist.

Both babies have been resourced by the system for the system’s own ends. Both babies have struggled to be themselves. Both babies have more in common than separates them. Both babies need to decide how a rattle or a rubber mallet can be most helpfully deployed in any given situation. And both babies need to remember that the 99% are only potentially the opposition to the 1% – unity has to be forged in a complex world of ambition, greed, diversion, abstraction, alienation, competing beliefs, diverse experiences of oppression and divide-and-rule.

Noone outside our own 0.1% are interested in the squabble between CD and CO (except those in the top 11% who wanted to promote the squabble for their own gain). I think the way forward is that we discuss “horses for courses”: how can each approach collaborate for the good of communities, so that we combine mass action with equal regard for Power and Empowering behaviour . We are starting to recognise mutually the plusses & drawbacks in all existing approaches:

• CD has loads of experience in putting values into practice within complex situations. CD has, in the UK, a track record of supporting long- term change and networking across places and identities. But it has suffered in many cases from co-option into the system (through salary & managerialism & targets) , and has been hit hard by cuts & hostility from the new Govt

• CO has proved its ability to inspire communities to become effectively active on common causes . But it struggles with limited training and no long-term focus on power dynamics and equalities issues within communities

Can we agree horses for causes/ a combination of approaches, given the demands of any situation ? Can we transcend one- size- fits- all or competing brands? Can we find shared roots in empowerment principles and independence from Govt?

Or shall we get a reinforced pram and go again?

Thanks Nick for such an interesting exploration of the subject. I would draw three main points from your analogy

1. The two approaches are vulnerable together but to start from hostility is both unhelpful and ultimately destructive; their mutual advantage lies in recognition not competition.

2. Faith in ‘the system’, the government (of whatever hue) or the people will not prove well-founded unless we are able to put in real work to raise consciousness of the threat we all face from the 1%.

3. Enough is shared for mutual respect and regard – focus on empowerment, shared roots, and as you say independence – without suggesting the two are the same; there remain fundamental differences in stance and style whilst the skills and practical appraoch may be pretty similar.

The horses for courses or combination needs to take account of the fundamental dissonance between a model that seeks to find the common ground between parties and to work for consensus (normally on what the powers can do for us) and one that focuses on the common good ‘inviting’ those who have lost touch with it (the oppressive minority) to return to the community and play their acountable part to bring about justice. Programme logic does impinge here, making those who have a outcome to deliver work with people in a distinctive way. And much CD in recent years – there are certainly exceptions – has been programme driven.

I’d value you further thoughts.

hi Mark,

1. Agree

2. Faith has to be in the people themselves, not in anyone else – the faith in their own potential to transform the world, not suffer in it. So I was playing with %s in the story because I think the threat is not just from the 1% – it is from many sources: eg. the far right (waiting in the wings for the alienated working class and middle class) , eg. from a culture which renders people dependent on external leadership and the belief that there is no alternative (hegemony) , eg. from a divided-and-ruled population. The real work is therefore long-term, patient dialogue on the deep issues, rooted in building relationships between peers from all backgrounds. It’s not about the worker or organiser – it’s about the shared process.

3. Agree, not the same – I’d love to explore the differences (programmes are not CD)

Mark said: 3. Enough is shared for mutual respect and regard – focus on empowerment, shared roots, and as you say independence – without suggesting the two are the same; there remain fundamental differences in stance and style whilst the skills and practical approach may be pretty similar.

Eileen – if the skills and practical approach are similar what is the significance of the fundamental differences in stance and style? Do they have any effect from and in their difference?

Mark said: The horses for courses or combination needs to take account of the fundamental dissonance between a model that seeks to find the common ground between parties and to work for consensus (normally on what the powers can do for us) and one that focuses on the common good ‘inviting’ those who have lost touch with it (the oppressive minority) to return to the community and play their accountable part to bring about justice.

Eileen: yes this is clear that sometimes the practices may be mutually exclusive. But for me one of the skills in community work whether called organising or development knows what is appropriate when. I feel more in line with Nick’s comments which like mine see a role for both and needing judgment as to when either is relevant. I get the impression from your comments that somehow you see an exclusive or excluding role for community organising. If this is not so I am not clear what we are discussing as we would then all be in agreement. But somehow I don’t feel we are agreeing. Hope for clarity to emerge sometime soon.

Mark – a useful overview account of a complicated and important area. I have only one quibble really and that is that it makes sense only if you put a capital C O for Community Organising and a capital C D for Community Development. As you know (me = a resident in your patch in Southwark), I am a community activist of many years. In my local activities in the local neighbourhood, I see myself as a community organiser (small co) who takes a community development (small cd) approach, and sometimes vice versa, as well as other roles I play all at once doing the same task often.

I think that the truth of your post comments lies in the vertical hierarchical system of policy makers, politicians and paid workers in the CO or CD field, and I can recognise a lot of it there, though not as a full description.

However, the complete distinction you make between these two fields does not equate with my full reality in the horizontal peer system on the ground for over 30 years, and misses out some of the perhaps most important reality on the street. Readers of this post can see the explanation for the references to vertical and horizontal systems in my paper on Community Engagement in the Social Eco-System Dance http://tinyurl.com/social-eco-system-dance-paper

available on the TSRC website. http://tinyurl.com/social-eco-system-dance

Hi Eileen – thanks for your interesting response. I feel you have missed though my later points about the key distinctions I see in organising. I am trying to press home the politicised nature of organising. In my view, organising is about developing an independent action network that stands in opposition to the power of the state and the market. It is made up of hundreds of individual citizens each coming to a growing awareness of the power in their lives. Such an ‘organisation’ creates a space for authentic democracy. Your distinction between CO and co is one I just don’t recognise as it is hard to find any distinction between volunteer community organisers and their neighbours, except that one group has a growing awareness of their situation and an eagerness to do something to improve it.

As you know, I think you have articulated the distinction between the two worlds accurately in your paper and appreciate you pointing to how it relates to this post. However, I don’t agree that there is a clear distinction between Community Organisers and community organisers. I would value your further comments.

Thanks Mark. I need to come back to this as I am out of time on other deadlines. Will not get to it now before next week possibly. But may see you in Preston. Will definitely respond though.

Hi Mark, thanks for an insightful post. Would you agree that another distinction is that CO emphasises voice (the powerless demanding their rights of the powerful) and that CD emphasises agency (the powerless acquiring power by helping themselves and each other)? Some time ago I asked colleagues who were involved in developing ICA’s approach to community development in Chicago in the 60s & 70s how they would distinguish it from that of from Alinsky’s in Chicago at that time, and that is how they responded. best wishes,

Martin

Hi Martin – thanks for this question. It certainly causes me to reflect on my experience of organising both with London Citizens and now with Locality. Two main responses come to mind.

1. Voice vs Agency I understand where this observation comes from. The effort to call powerful agents to account is certainly part of the organising tradition. As I have been taught it, the framework is that the people with their diverse interests discover together what the common good is in any specific situation. They use debate and democratic means to reach as clear a consensus as possible. This agenda then becomes the means whereby the powerful can be assessed – do their policies and practice support and extend the common good? Where they fail the test, then the people have the responsibility to call them to account. The people are organised to use their numerical power to bear on the financial power of the elite. The call to the powerful then is not for the fulfilment of rights (an alien concept in 1960s and 1970s) but rather to enter back into the right relationship with the community of which they are a part; they should use their power to deliver the common good rather than to enhance their private benefit.

I think many US organising agencies have tried to also deliver programmes (agency in your terms) and have come apart at the seams. They have tried to live with the system as it is and to remodel it from inside. The staff and supporters of such an approach have failed to make the transition from working together to change the system fundamentally to working together to improve the system incrementally.

2. Organising is centrally about self-interest. That is distinct from selfishness (the self above all others) or selflessness (the many above self). Self interest brings the individual into relationship with the community in such a way that both benefit from the relationship. In this way, organising is as much about people taking charge of their own lives and ‘helping themselves’ as CD. It starts – IMHO – from a more realistic base that we are competing for limited resources and that the powerful have changed the rules in their favour. When we organise to find our common ground, we are able to challenge them in many ways – some of those will be by developing alternative power such as our own initiatives, businesses, enterprises and projects – self-help if you like.

I hope this is a helpful response and look forward to your ideas in reply.

Martin’s distinction: “CO emphasises voice (the powerless demanding their rights of the powerful) and that CD emphasises agency (the powerless acquiring power by helping themselves and each other)” is an interesting one but makes me clear that we are doing both within the current Community Organisers programme (http://cocollaborative.org.uk). We always say that COs listen to people, build networks and encourage them to take action, and that action might be to change the powerful, it might be a self-help response, or it might be a combination of both. To me the crucial thing is the listening and the network-building at grassroots. I’ve seen so many CD workers in meetings with each other, and so few out and about on the streets. We’ve been warned that COs must understand “what’s already there”, but the best way to know that is not to go to meetings but to focus on residents themselves – if what’s already there is reaching them they will no doubt mention it…

Thanks for joining the discussion, Jess. I would echo your observation that listening to citizens’ views about their lives, what hurts and hinders them as well as what they dream of for their community is fundamental to organising. I nearly added a third point to the post about the importance of listening but it was getting long already and I was sure my CD colleagues would immediately say they were listening as well. The focus on open-ended encounters of depth with people of all sorts and types is central to all organising – probing for the moment when the individual is ready to be challenged to take a greater part in their community’s life. The street level view is quite different to that of agency staff and the concerns are so utterly different to those addressed by government programmes. People want decent homes, safe places for their kids to play and good jobs; too much of the dialogue in meetings loses focus and gains a unnecessary complexity. I have already written about the avoidance of links to organisations that is a strong emphasis of both Locality and London Citizens. The goal is practical action on the ground, driven by the priorities of residents.

hiya, the distinction between CD and CO isn’t about being on the streets – street work belongs to no single tradition. As a CD worker I spent ten years based in the estate’s community centre (campaigned for by the people, built by the people for the people, and antagonising my employers in the process) and working every day in the streets, at the school-gates, in people’s houses, on the park, knowing that we had a great place to meet collectively in the community’s own building when we needed it (it would have been nice to spend some time with other CD workers to reflect on what we’re doing, mind, but worker’s meetings were limited to two hours a month). It would be great to see us combining all the qualities of CD and CO in a shared approach out there on the streets (rather than peeing on lamp-posts)

Hypostasising about CO and CD is all well and good at a certain level but it’s hardly relevant at deprived neighbourhood level, where the community organisers, presumably, will be operating, is it?

With only 8% (or is it 7% or 6%) of the cuts so far in place, local-authority community development workers among the first to get the chop, services disappearing, benefits being squeezed, unemployment rising and no prospects getting better in the foreseeable future, the community-level neighbourhood groups are, to put it mildly, under pressure – the small grants to keep on keeping on are a thing of the past for most of them.

How effective the community organisers can be will depend, to a large degree, on their training. So how well trained will they be?

Mark, I think you had a masters in community organising (was it a couple of years full time at university and six months with London Citizens?) before you started on the government programme?: Will the CO training (was it two days with online support you got from Regenerate Trust?) adequately equip the CO’s to do the job?

Cheers, Joe

Just for accuracy, Joe, the CO training begins with a 3.5 day intensive residential which is followed by six months of learning on the job which includes four x 5-hour live online sessions with the whole cohort plus one or two guided action visits. The second six months of the CO’s training period offers a range of options to ‘Go Deeper’, either for further accreditation or in non-accredited practice-based areas of interest such as Digital Organising and Assets & Enterprise. All the time they continue their work and learning at the local level. We are introducing further monthly learning support online sessions for groups of 8-10 COs. Most of the COs also communicate all the time on their private Yammer network. The dynamic peer learning and mutual support and challenge that this ovwerall approach enables is incredibly valuable and something that was practically impossible to achieve when Alinsky described the long-haul of training as all about sitting in rooms for weeks on end.

While I have huge respect for Mark’s knowledge gained through university and London Citizens I am sure he would agree that there are others currently training who will be are as good or even better than he is at organising on the ground. It really doesn’t take university to make a brilliant community organiser.

In the dim past some theologians spent a lot of time and energy arguing about how many angels could you get on the point of a needle. As I recall the angels were busy at the time trying to get a rich man through the eye of the said needle!

There is a temptation to put energy into seeking a purity of language around this stuff that can delay actually challenging things that need challenging. Governments (certainly in the last 30 years) have been re-badging things after having strategic rhetoric development which then becomes the language of the institutions that continue to exist for there own purpose. I’m not complaining about this as I made a decent living out of thinking I was doing something when I was so busy working out what ’empowerment’ meant.

A time is coming when what something is called or described as will be irrelevant. Global warming, the overwhelming power of corporations, population growth, running out of stuff we dig out of the ground, ageing populations and declining ways of supporting them are just a few of the things that are facing us bugs scrabbling around on this little blue-green planet, spinning around an unimportant star, in the least fashionable end of a spiral arm of the milky way.

It’s way past time to carry on re-cycling stuff that’s been going on amongst and between humans since we arrived. It’s time for a new dialogue, It’s time for a new way of working together, a new collective. Lets consume differently, let’s secure our food, let’s explore how we balance collaboration and competition, and how we can improve democracy and enfranchisement. Lets prototype new ways of living in community and make decisions about resources.

I’m not sure that a top down initiative will bring about the nirvana we seek, not with the current system, the same approaches that we’ve been doing for years. I don’t have any particular answers other than: let’s dream.

Everybody is missing one vital ingredient:- CO or CD isn’t the point, once the dust settles following the forthcoming welfare and social housing reforms, every “deprived” neighbourhood in England will look very different to now. Demographics will be turned upside down and many longer term community activists will inevitably be forced to move elsewhere to live(Underoccupation reductions to beneifts etc). There may be no social capital left there for the COs to work with.

Joe is correct in his assumption that with austerity induced LA cuts to small grants for community groups many have already disappeared whilst those remaining are struggling to achieve very little in effect.

Trust is completely exhausted and most residents are really struggling to survive from day to day.

People today are no longer interested in wider networking of designing new areas to participate in through power imbalanced social /voluntary partnerships .

Whether CO or CD nobody will be in a position to persuade the local residents to listen to any other viewpoint other than their own locally defined requirements—Localism -only people living locally can take control through Neighbourhood Planning and exerting more influence on strategic (particularly Housing ) policy making as defined in the Localism Act . All else is irrelevant to these activists , many of whom no longer engage with the historic engagement processes as they no longer trust the statutory partners..including politicians and the VCS , let alone those considered consultants with possible vested interests.

Nobody can empower anyone else…Power can only be seized ….and there lies the real problem .

How can COs guarantee that their total neutrality will help local residents to achieve the political step change they consider necessary to improve their own lives and their own neighbourhoods?

I fear many COs will quickly find themselves marginalised by those very experienced activists , most of whom will be much better informed than this trained CO army and many will also be much more effective locally and already have the full support and respect of their peers on whose behalf they have worked voluntarily often for many years.

Community organisations are not service providers…and 99% never will be.

So, what’s the ‘Campaign for Community Development’ all about? Quote:

“The Campaign for Community Development will be inseparably linked to campaigns against the cuts and support for the struggles of communities. It goes far broader than recognition for Community Development and against the community development job losses that are already taking place.”

And perhaps in this we see the seeds of this campaigns own destruction – a politicised stance that takes the views of others as read. An excellent example of where CD can go badly wrong.